In theater, the viewers are often far from the action, and lighting is not always perfect. To make sure everyone can see what’s going on – even the people in the last row who might not be paying that close attention – theaters around the world have developed distinct styles of make-up to

communicate performances clearly to people in the back.

Beijing opera in China.

Kabuki theatre in Japan.

Commedia dell’arte from Europe.

Broadway in the US.

And burlesque.

The task faced by posters is much the same. You have to communicate to people in the “back row.”

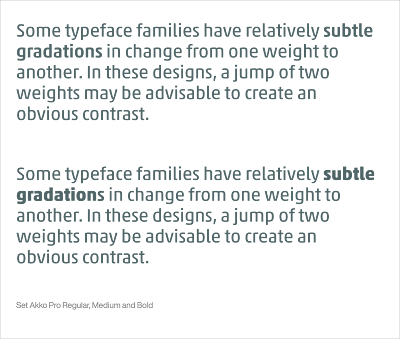

This is a graph with no make-up. Click to enlarge!

This graph might be just fine in a printed journal. Everything is there. It’s high resolution, and would probably look just fine if professionally printed. But put that on a poster, and it will vanish, just like a stage performer without make-up seen from the back row.

This is a version of the graph that reaches out to the person in the back row.

The biggest change is filling the box with a colour, so now the box reads from a greater distance. The symbols are bigger. The lines are thicker both around the box and in the very wide whisker caps.

But the graph above might be a case of “everything louder than everything else” (to borrow a phrase from

Jim Steinmann). It is definitely visible from a distance, but might be too much. There is no visual hierarchy that emphasizes the point.

The point of make-up isn’t to make everything bigger. It

focuses and emphasizes. Usually that means drawing attention to the eyes and mouth. Make-up isn’t

supposed to emphasize your lines, your pimples, your age spots, or pores. Indeed,

de-emphasizing some features is one of the major attractions of make-up for many people.

Make-up and graphic design bring emphasis using some of the same tricks: colour, contrast, and size. Whatever you want to highlight, might it colourful, high contrast, and a little bigger.

Let’s say that you wanted people to be able to quickly see the averages in your box plot. You might make a graph a little more like this.

The saturated red symbol for the average pops out from the background. You can see those symbols from the back row.

Reordering the bars helps to show a pattern in data.

The boxes are still filled and still visible from a distance, but the making them more pale means that they are more visible in a close read: someone who comes right up to the poster and wants to see details.

The whisker caps are thin for the same reason.

But what if you wanted to emphasize the

range of data instead of the central tendency? You would emphasize different parts of the box plot.

The whiskers end in high contrast symbols that bracket the range of data. Now your attention is drawn to the maximum and minimum.

The boxes are still filled, but are thinner to emphasize continuity with the whiskers.

I did not tinker with the axes at all in any of these. I wanted to focus on the presentation of the data. There is surely more that could be done to make-over the axes and labels so they would be more appropriate for a poster.

So when you are doing “make-up” on your graph, ask yourself:

- What do you want to emphasize? (“Everything” is not a valid answer!)

- Does it reach the person in the back row?

Beijing opera picture from here. Commedia dell’Arte photo from here. Kabuki photo from here. Nala makeup from here. Burlesque make-up by Frankie Fictitious.

This post inspired by Justin Stewart.