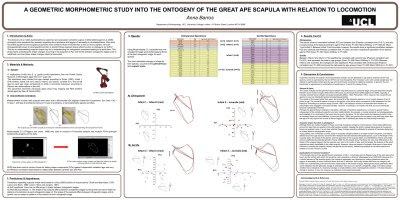

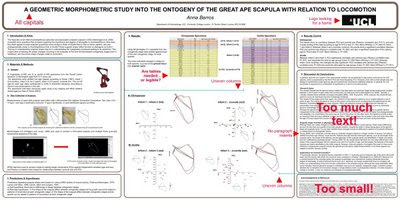

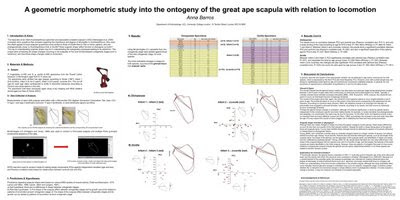

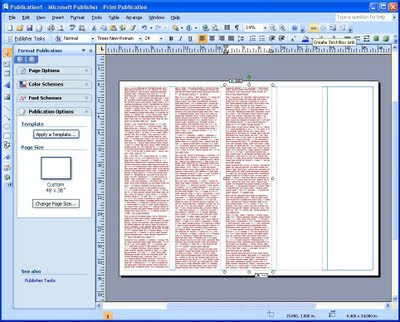

To help diagnose whether your poster is ready to print or ready to trash, I’ve devised a Better Posters checklist. You can click to enlarge. The enlarged checklist is readable, but I suspect what you really want is the high quality, printable PDF version.

This checklist was based on and inspired by the Glance Test for slides created by Nancy Duarte and Glenn Hughes. Steal from the best, I always say.

I hope that this tool will help you fulfill what should be a New Year’s resolution:

“No more ugly conference posters!”

Updated, 27 September 2017: Link to PDF repaired! Thanks to Natalia Asari for the nudge! I suppose I should also point out that this might be a useful starting point for judges who want to rate posters for a competition.

Update, 21 May 2022: I’ve updated the PDF for 2022. It no longer looks like the image above, because the original became unavailable to me when I changed institutions. I had to rebuild it from the image here on the blog. While doing so, I made some changes that I hope will make it more usable.

This new 2022 version is now stored on Figshare, so should remain stable.External links

Better Posters checlist in PDF form on Figshare